As well as working in the industry, I am first and foremost a fan of films. Films are just as capable of articulating the world (inner and outer) as any other art form 1. I’m taking it upon myself to defend a film which will undoubtedly appear on many Worst of 2006 lists, which is a shame.

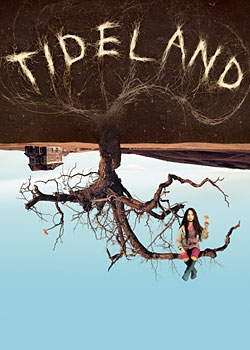

Tideland is a film by Terry Gilliam, a director who has a reputation for being a maverick. He packs his work with unbridled fits of imagination and passion – often much to the chagrin of his investors. One only needs to research the making of films such as The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), Brazil (1985), and more recently his unfinished Don Quixote project 2 to understand that this is someone who doesn’t listen to reason if reason gets in the way of a neat idea. Tideland is no exception.

Though released only weeks ago it was actually completed in 2005 and spent a long time floating around festivals until it dropped into theatres unceremoniously in October. With few exceptions the film was summarily eviscerated by the critics and subsequently shunned by the movie-going public. It will go on Gilliam’s track record as yet another “ambitious failure” 3.

I’m here to say that I’ve seen Tideland, and it’s good. Beguiling at times, but good. The story concerns Jeliza-Rose (Jodelle Ferland), a ten-year-old girl whose abusive mother dies of a drug-overdose. Escaping the city with her scallywag father (played by Jeff Bridges), they wind up at a ramshackle house in the middle of the prairie that once belonged to her grandmother. It has since been abandoned and pretty soon – after her father suffers from a fate similar to her mother – Jeliza-Rose is left alone to fend for herself. The greatest weapon at her disposal, however, is a seemingly bottomless imagination (her friends, from the beginning of the film, are three doll heads she fits onto her fingers and engages in conversation with). Along the way, she encounters her neighbours (which, on the prairie, means a mile away), Dell and Dickens, a rather odd brother and sister; she (played by Janet McTeer) is a taxidermist with a witch-like demeanor and a dire fear of bees. Her brother (wonderfully rendered by Brendan Fletcher) had his brain operated on long ago to counter epilepsy and seems to be more child than man. Dickens and Jeliza-Rose becomes close friends, seemingly mental and emotional equals.

As much as I don’t like to say what a film (or any piece of art) is “about”, it’s clear – particularly given Gilliam’s repertoire – that one of the key messages of the film deals with the power of imagination in the face of bleakness. It is a bleak story, I won’t kid you (in case my synopsis didn’t get it across). However, the key difference between Gilliam and other directors is that his philosophy is never misanthropic; he always shows us a type of reality that is equal parts magical and bittersweet. Jodelle Ferland’s performance is this best I’ve seen this year and an astounding achievement for a child of her age; she is able to render the inner world and perspective of her character without ever being less than convincing.

I went into this film expecting a stinker and I walked away with a lot of haunting questions about childhood and the resilience of imagination. It’s a fair criticism to say that, in a film that so intimately (and disturbingly) inhabits a child’s world, there could have been an injection of objective perspective so that the audience had a better sense of what was real and what was fantasy. However, aside from that, the film stands comfortably on its own and proudly – in my opinion – beside the best of Gilliam’s work. This makes it all the more unfortunate that it got trounced in its theatrical release. While not the first time Gilliam has experienced such disappointment, it seems the price he has had to pay to give us some of the most inspiring and wild flights of fancy.

1. It was Sergei Eisenstein who said that editing is the only art form native to filmmaking (all its other elements originating in either theatre or photography)

2. See: Lost in La Mancha

3. Aside from Munchausen which reported a record-loss in its day, his last feature, The Grimm Brothers was characterized by the sort of producer-led sabotage the Weinstein brothers are famous for. It’s not a very good film and I don’t quite understand what the intent was behind it – but that’s another story. I’m a champion of Gilliam but I won’t stop short of staring at Grimm suspiciously.