Whenever a mental health authority is interviewed in the media it’s nearly inevitable that this person is a medical doctor, usually a psychiatrist. This individual typically isn’t a practicing therapist; they may only be able to speak of clinical diagnoses and/or the prescription of psychopharmaceuticals. I mention this because when this authoritative psychiatrist is interviewed in the media I end up listening to a depiction of the massively complex human interrelational landscape I see around me every day, as both a writer and psychotherapist, reduced to a chemical imbalance in someone’s brain. It’s like ascribing a boxer’s loss of a title match solely to the width of their biceps.

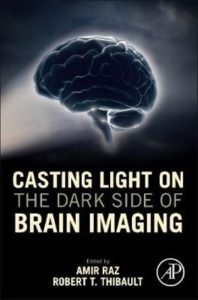

The gold standard for looking at mental health is through what’s called a biopsychosocial lens, a flexible model that allows professionals to consider the biomedical (for example, thyroid issues, dementia), the psychological (traumatic experiences, abusive relationships), and socio-economic factors (unemployment, impoverished environment) that might be at play in the mental health profile of any given individual, even if it ends up a combination of one or more parts. In North America there is unfortunately a sacred primacy around the biomedical approach to mental health, with the psychological and socio-economic as (at best) secondary considerations at the table of funding and education. At this moment there are medical doctors losing sleep wondering how to beat the shame of knowing there is a patient in their care whose condition might be psychogenic (meaning, whose pathology is not, strictly speaking, a biomedical end product). Continue reading “Book Review: Casting Light on the Dark Side of Brain Imaging”

The gold standard for looking at mental health is through what’s called a biopsychosocial lens, a flexible model that allows professionals to consider the biomedical (for example, thyroid issues, dementia), the psychological (traumatic experiences, abusive relationships), and socio-economic factors (unemployment, impoverished environment) that might be at play in the mental health profile of any given individual, even if it ends up a combination of one or more parts. In North America there is unfortunately a sacred primacy around the biomedical approach to mental health, with the psychological and socio-economic as (at best) secondary considerations at the table of funding and education. At this moment there are medical doctors losing sleep wondering how to beat the shame of knowing there is a patient in their care whose condition might be psychogenic (meaning, whose pathology is not, strictly speaking, a biomedical end product). Continue reading “Book Review: Casting Light on the Dark Side of Brain Imaging”

I’ve noticed more and more over the last decade that less and less people want to use the phone. I cannot help but draw a correlation between this observation and the ubiquitous rise of digital communication. Email? Sure. Text? Yup. And what’s wrong with this, you might ask? On paper it would objectively appear that text-based communication (particularly including social media) is superior at transferring information without error, if only us pesky humans didn’t make mistakes. And this last part is key: we are not objective, we balance the objective world with our much less easily measurable experiential (or personal) reality; this second reality is informed by our experiences, which are diverse and sometimes punctuated by trauma or loss. When we talk to someone on the phone we are leaving ourselves prone — to fallibility (stammering, going off on a tangent), or having our hesitations read as something we may not otherwise wish to reveal.

I’ve noticed more and more over the last decade that less and less people want to use the phone. I cannot help but draw a correlation between this observation and the ubiquitous rise of digital communication. Email? Sure. Text? Yup. And what’s wrong with this, you might ask? On paper it would objectively appear that text-based communication (particularly including social media) is superior at transferring information without error, if only us pesky humans didn’t make mistakes. And this last part is key: we are not objective, we balance the objective world with our much less easily measurable experiential (or personal) reality; this second reality is informed by our experiences, which are diverse and sometimes punctuated by trauma or loss. When we talk to someone on the phone we are leaving ourselves prone — to fallibility (stammering, going off on a tangent), or having our hesitations read as something we may not otherwise wish to reveal.

It’s hard to keep everything together in one cohesive piece, and I realize that the only way anyone would know I’m on

It’s hard to keep everything together in one cohesive piece, and I realize that the only way anyone would know I’m on