I used to hang-out in cafés when I was in my early twenties. It was a means to get out of the house without going to bars. Chances were, the conversations were better in cafés, and – depending upon the type of café – the people were usually a little more sophisticated [why writing that word feels like an elitist thing, I’m not sure – is there something wrong with sophistication?]. Most of all, cafés are cheaper than bars, and when you’re in college and starving, it made sense to choose the former if you wanted to avoid the bottleneck of debt.

There was a place in Burlington (Ontario, sorry Vermont) which lasted perhaps only a year (as all good things die early in Burlington, including the dreams of its youth…but I digress). I can’t even remember the name – French, I think. The owner was a very interesting fellow, an accomplished academic who’d lived and studied in Paris previously. I’m not sure how he managed to  afford a café in the middle of a very chi chi shopping square, but he made the best of it: poetry readings, live music, parties. It was all very fin de siècle; nothing like that can live for very long in a town as complacent and suburban as Burlington was at the time.

afford a café in the middle of a very chi chi shopping square, but he made the best of it: poetry readings, live music, parties. It was all very fin de siècle; nothing like that can live for very long in a town as complacent and suburban as Burlington was at the time.

I remember one afternoon, sitting with him (his name escapes me…so much of the years from 1990 -> 1995 escape me), and chatting. The topic arose of translation. He revealed that he wrote about the aesthetics and potential controversies of translation. Can you imagine having a book published about translation? I couldn’t then – it was something I simply took for granted and sometimes still do. The more we talked, the more I realised how much blind trust we put in the hands of the person whose job it is to convert the prose of the world’s great non-English-speaking writers. It never crosses our minds that a translator could be culturally prejudiced, or simply unimaginative for that matter.

Let’s face it: when I recently read Crime and Punishment I didn’t hesitate to think that I was reading anything but the prose of Fyodor Dostoevsky. But, of course, it was a translation. I can only assume it was accurate, not that I would have any way to tell as I only have an elementary understanding of Cyrillic (let alone Russian). What is astounding to me, is to think of how effortless and transparent the best translations are – when I consider the acrobatics some of them must go through in order to preserve the magic of the original text (the rhythm, the flow, the style, the weight, the economy) I always conclude that it must be such a rewarding and paradoxically unheralded role to play. Who translated the copy of Crime and Punishment that I just finished reading? Couldn’t tell you. I didn’t look.

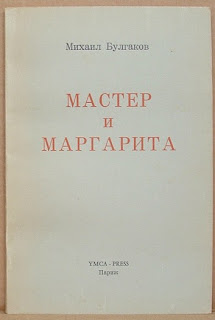

This was brought to my attention most recently, and most magically, with the appearance of the book The Master and Margarita in my life. I was speaking with a Russian composer one day, relating how much I enjoyed speculative fiction from former-Soviet countries (Stanislaw Lem, the Strugatsky brothers…) when he mentioned, “Have you read Master and Margarita, by Bulgakov?”. “Who??” was my response. Let’s face it, Bulgakov is not a name etched in the collective memory of popular literature. “You must read Master and Margarita.” was all he said, with that particularly curt Slavic insistence which intones the inherent universal importance of whatever it is that’s being recommended, without question. So, I went on my laptop and did some searching – what I found was that there were, at last count, five English translations of the book.

Five.

As it turned-out, one was based on the censored Soviet text, another was marked as simply not in-depth enough, with three more ranging in response from capable to great. So – aware of the inherent importance of translation and having my curiosity piqued by the book itself – I did more research and found that the most recent translation had been done in 2006 by a fellow Canadian, Michael Karpelson (highlighted in this article from an otherwise obscure right-wing news site). To make a long story short, this translation was self-published through LuLu.com and was off-line due to small revisions Karpelson wanted to make. I ended up getting his email address from LuLu and contacted him directly – he was very nice and offered to sell me a copy from the existing print run. By the time I received it, I had no less than five other people, without prompting, ask whether I’d read the book. Talk about destiny.

due to small revisions Karpelson wanted to make. I ended up getting his email address from LuLu and contacted him directly – he was very nice and offered to sell me a copy from the existing print run. By the time I received it, I had no less than five other people, without prompting, ask whether I’d read the book. Talk about destiny.

So, for the Michael Karpelson’s of the literary world, without whom authors as diverse as Camus, Marquez, Borges, and the Dalai Lama would have no means to speak to English-speaking readers, I raise a toast of appreciation.

[note: I will have a proper review of The Master and Margarita within the next week or so]

Really insightful comments. You’ve got me intrigued by Master and Margarita.

Thanks Tina – I finished it a few days ago, and it truly is a great book. Seems to be making a resurgence these days also.