Here’s the best of what I’ve seen this year. I haven’t seen everything. You may disagree with what I have seen. This is life.

FILM:

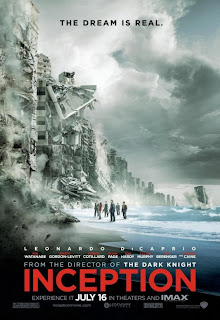

Inception

Go ahead. Try. Try disagreeing that this is one of the most technically (and perhaps conceptually) elaborate mainstream Hollywood productions released in years which also happens to work as a “movie” that a wide variety of audiences would enjoy watching.

There has been a backlash against Inception. I don’t know how or why this is – perhaps it was over-sold as a deep “puzzle-solver” film, which it is not. And yes, the NYT’s A.O. Scott has a point in his comment that the film’s literal depiction of dreams are lacking psychological heft (outside of Marion Cotillard’s performance as DiCaprio’s wife). In any case, something has caused a revolt against this film and I say this revolt is missing the point.

Inception is, generally speaking, the most watchable, the most fascinating film of 2010. You are allowed to hate it.

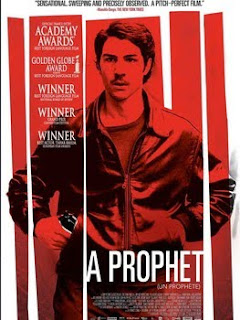

A Prophet

I am a huge fan of Jacques Audiard, a French director who has always rewarded the viewer with films (Read My Lips, The Beat My Heart Skipped) that balance passion with style. With A Prophet, Audiard expands his canvas, creating a gritty, novelistic masterpiece on-par with The Godfather (yes). The story concerns a young incarcerated Muslim who slowly rebuilds himself from within the treachery of prison life, rising from under the thumb of a vicious mob leader to become his own person and create his own empire. Epic, patient, and in places extremely violent. People will be referring to this film for years to come even if it has not really made a mark in North America. Again, a masterpiece.

The Eclipse

I realize this Irish film was released in 2009, but it didn’t get here until now. A compelling ghost story which eschews the two-dimensionality of ghost story films. It was around the twenty-minute mark that I realized it was a film which was going to confound my expectations (expectations based upon years and hundreds of similar plot lines): it wasn’t going to squander what it was and fall prey to hackneyed cliché. A gorgeous, touching, ultimately humanistic film with a stand-out performance by Ciarán Hinds as a grieving father of two children who must swallow his pride to escort a loud-mouthed Aidan Quinn through the motions of a book tour of the small coastal city of Cobh, in County Cork. A sublime achievement by director Conor McPherson.

Notable: Winter’s Bone – see it. It’s on DVD now. Like A Simple Plan, it’s a self-contained “rural thriller” (ugh) with a chilling undertone of barren hopelessness. Unlike A Simple Plan, it’s uncomplicated which is what gives it more of an honest strength. Exit Through The Gift Shop is the perhaps best film made about art and the art world that I have seen – like Inception, it’s not trying to be deep, just smart. Scott Pilgrim vs. The World blew me away because I expected it to be weak (perhaps because all the publicity photos inexplicably used a static image of Michael Cera standing against a fucking wall…imagine if you will, trying to sell Star Wars with a picture of Mark Hamill sitting cross-legged in the desert – sounds awesome, eh?). Not only was it not weak, it was the strangest case of “I don’t know why I love this movie but I really do”. Painstakingly, sublimely Toronto-centric (which, unlike the inexplicable promo photos of Michael Cera, shouldn’t be factored into explaining why it didn’t fare well at the box office) and wildly imaginative – those two things have never met before…oh but wait, I forgot the perfect companion piece: Kick Ass – also shot in TO, and also exceedingly expectation-defying (although the climax is kinda drawn-out). As far as performances go, Jesse Eisenberg (The Social Network) and Colin Firth (The King’s Speech) stand out, along with Winter’s Bone‘s Jennifer Lawrence, and Hailee Steinfeld for True Grit (who, at 14-years, shows huge promise as an actor).

BOOK:

I would have said “BOOKS”, but due to work and school I haven’t read anything published this year (that I can remember), with the exception of John Vaillant’s The Tiger. Lucky for me, since it is without doubt one of the best non-fiction titles I’ve read in years.

The Tiger is a meaty real-life tale of vengeance by the titular beast, in the winter hinterland of the Russian Far East (which the author calls, paradoxically, “the boreal forest”). Vaillant describes an environment historically, politically, and biologically unique, inhabited by hardened outcasts. The shadow of a predator male tiger, known never before to attack without cause, creates a wave of dread throughout the land, with only a small band of volunteers to figure out the mystery. Vaillant provides wave after wave of fascinating detail – examples of how man and beast have evolved throughout time, how human and animal behaviour have worked in similar paths – that by the end of the book you feel as if you should have a credit in Ethology. This is truly a page-turner and I cannot recommend it enough.