(Yes…I know it’s May. Don’t take me so literally.)

One of the most captivating songs – a song that seems destined to have an everlasting power, despite a gaggle of jazz performers hanging their hat on it to fill out an album or hope upon hope for a Billboard spot – is a bossa nova piece, originally written by Antonio Carlos Jobim in 1972, called Waters of March (or Águas de Março in its native Portuguese). Remarkably, one of the definitive versions (although there are so many beautiful renditions) is captured on YouTube here, performed by Elis Regina. [sidenote: watch this side-by-side with the early 80’s video for Every Breath You Take by The Police – the similarities in the look, style, direction, and editing are uncanny]

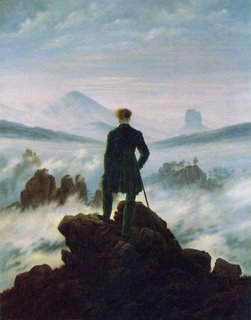

What I love about the song, ever since I first became aware of it long, long ago (and still, it took me years to find the name of the song – I was convinced that Astrud “The Girl From Ipanema” Gilberto had done it originally, which turned out to be a red herring…as so many things I’d naively attributed to her – but that’s another story) is its flow and stream of consciousness; considering it was written during Rio de Janeiro’s downpours in late March – the end of summer in the Southern Hemisphere – it’s a stunning bit of onomatopoeia.

Though originally written in Portuguese – the language of Brazil, for all you junior ranchers out there – Jobim eventually re-worked the lyrics into an English translation which is actually longer (which was necessary to keep the feel/structure of the original). For more information on this song, please see this entry in Wikipedia.

Here are the Portuguese lyrics and their English re-working:

Águas de Março

“É pau, é pedra,

é o fim do caminho

É um resto de toco,

é um pouco sozinhoÉ um caco de vidro,

é a vida, é o sol

É a noite, é a morte,

é o laço, é o anzolÉ peroba do campo,

é o nó da madeira

Caingá candeia,

é o matita-pereiraÉ madeira de vento,

tombo da ribanceira

É o mistério profundo,

é o queira ou não queiraÉ o vento ventando,

é o fim da ladeira

É a viga, é o vão,

festa da cumeeiraÉ a chuva chovendo,

é conversa ribeira

Das águas de março,

é o fim da canseiraÉ o pé, é o chão,

é a marcha estradeira

Passarinho na mão,

pedra de atiradeiraÉ uma ave no céu,

é uma ave no chão

É um regato, é uma fonte,

é um pedaço de pãoÉ o fundo do poço,

é o fim do caminho

No rosto o desgosto,

é um pouco sozinhoÉ um estrepe, é um prego,

é uma ponta, é um ponto

É um pingo pingando,

é uma conta, é um contoÉ um peixe, é um gesto,

é uma prata brilhando

É a luz da manhã,

é o tijolo chegandoÉ a lenha, é o dia,

é o fim da picada

É a garrafa de cana,

o estilhaço na estradaÉ o projeto da casa,

é o corpo na cama

É o carro enguiçado,

é a lama, é a lamaÉ um passo, é uma ponte,

é um sapo, é uma rã

É um resto de mato,

na luz da manhãSão as águas de março

fechando o verão

É a promessa de vida

no teu coraçãoÉ uma cobra, é um pau,

é João, é José

É um espinho na mão,

é um corte no péSão as águas de março

fechando o verão

É a promessa de vida

no teu coraçãoÉ pau, é pedra,

é o fim do caminho

É um resto de toco,

é um pouco sozinhoÉ um passo, é uma ponte,

é um sapo, é uma rã

É um belo horizonte,

é uma febre terçãSão as águas de março

fechando o verão

É a promessa de vida

no teu coração”

Waters of March

A stick, a stone,

It’s the end of the road,

It’s the rest of a stump,

It’s a little aloneIt’s a sliver of glass,

It is life, it’s the sun,

It is night, it is death,

It’s a trap, it’s a gunThe oak when it blooms,

A fox in the brush,

A knot in the wood,

The song of a thrushThe wood of the wind,

A cliff, a fall,

A scratch, a lump,

It is nothing at allIt’s the wind blowing free,

It’s the end of the slope,

It’s a beam, it’s a void,

It’s a hunch, it’s a hopeAnd the river bank talks

of the waters of March,

It’s the end of the strain,

The joy in your heartThe foot, the ground,

The flesh and the bone,

The beat of the road,

A slingshot’s stoneA fish, a flash,

A silvery glow,

A fight, a bet,

The range of a bowThe bed of the well,

The end of the line,

The dismay in the face,

It’s a loss, it’s a findA spear, a spike,

A point, a nail,

A drip, a drop,

The end of the taleA truckload of bricks

in the soft morning light,

The shot of a gun

in the dead of the nightA mile, a must,

A thrust, a bump,

It’s a girl, it’s a rhyme,

It’s a cold, it’s the mumpsThe plan of the house,

The body in bed,

And the car that got stuck,

It’s the mud, it’s the mudAfloat, adrift,

A flight, a wing,

A hawk, a quail,

The promise of springAnd the riverbank talks

of the waters of March,

It’s the promise of life

It’s the joy in your heartA stick, a stone,

It’s the end of the road

It’s the rest of a stump,

It’s a little aloneA snake, a stick,

It is John, it is Joe,

It’s a thorn in your hand

and a cut in your toeA point, a grain,

A bee, a bite,

A blink, a buzzard,

A sudden stroke of nightA pin, a needle,

A sting, a pain,

A snail, a riddle,

A wasp, a stainA pass in the mountains,

A horse and a mule,

In the distance the shelves

rode three shadows of blueAnd the riverbank talks

of the waters of March,

It’s the promise of life

in your heart, in your heartA stick, a stone,

The end of the road,

The rest of a stump,

A lonesome roadA sliver of glass,

A life, the sun,

A knife, a death,

The end of the runAnd the riverbank talks

of the waters of March,

It’s the end of all strain,

It’s the joy in your heart.