I don’t know how or when I got into ambient music. I can tell you there have been a few seminal contributors: classical music, movie soundtracks, minimalist and so-called world music composers, and the more spacious actors in pop/rock music.

Let’s start with a sort-of definition of ambient music, and I will begin by saying that I have no formal education in this realm. Ambient music is typically experimental and tends toward spaciousness and a lack of traditional (Western) song structure; it has its roots in the likes of 20th century composers such as John Cage, as well, during its development, contributions from traditional music from India and Japan, as well as from jazz. It can be a formless and electronic haze, or it could be all about exacting pattern and repetition using traditional instrumentation. There is also often a sense of the tactile. I will include some examples toward the end of this piece to begin to provide some context. At the end of the day, what is and isn’t strictly termed “ambient” is often more a question of the composer’s intent. You will just as likely see genre labels such as “minimalist,” “drone,” and “experimental” instead, as the term “ambient” can be a sort of kludge.

As a primary influence on me, classical music is a no-brainer, and like a lot of kids who grew up at the time I did, we were treated (or as I like to say, inculcated) to classical music through Bugs Bunny and Disney cartoons. As an adult I love the flourish and bombast of Shostakovich and Borodin, and the aching lyricism of Vivaldi and Bach. However, there is something undeniably mesmerizing about a brief section of Act II of Wagner’s opera Siegfried, where, through gorgeous use of instrumentation and dynamics we are surrounded by the quiet stirrings of nature — it surrounds the listener and one has no choice but to surrender to its formlessness. This formlessness is not something we often associate with something so strictly structured as classical* music.

As a movie buff, it makes perfect sense, given my exposure to classical music as a child, that movie soundtracks would inspire my appreciation of ambient music. Even in an epic space opera such as The Emperor Strikes Back there are many moments — particularly the suspenseful, quiet bits — where John Williams draws from classical roots, but of course, in order to create mood and retain timbre, sections end up as long stretches of almost abstract-sounding composition. Another perfect example would be the use of György Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey during the monolith scenes. Funny how sci-fi tends toward this direction.

A movie and a soundtrack that shook my foundations as a teenager was Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi. While the imagery was both disturbing and inventive, it was my introduction to Philip Glass’ minimalist composition that entranced me. Its mantric dedication to repetition using an orchestral ensemble and use of church organ and choir during its more climactic parts was catnip to this kid. When, a year or so later after seeing this, I discovered that Glass had collaborated on an album with Ravi Shankar (1990’s Passages) I couldn’t resist picking up a copy at a classical/jazz record shop near where I worked as a photolab technician. It was love at first listen; while some might’ve thought that the two were at odds with each other — one an avant-garde composer, the other an Indian classicist — their collaboration (each took turns orchestrating the other’s compositions) was a major influence on me.

To save space here, I will briefly name three other significant musical influences: David Sylvian, Talk Talk, and Miles Davis. Sylvian’s Japan reunion of-sorts, Rain Tree Crow, only put out one album but it was a low-key combination of rock/jazz/experimental soundscapes with African rhythms that has had a lasting influence on how I decided to listen to music. Talk Talk’s last two albums — Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock — are rightly hailed as experimental masterpieces of pop-meets-improv jazz however a single song deserves mention, from their comparatively more formal pop album The Colour of Spring: April 5th. You can see where they were going with only that one song (and the album is wonderful as it is). Lastly, discovering Miles Davis’ album In A Silent Way was another key piece in my ad hoc self-education: the tactile nature of the instrumentation has been hugely influential on composers of all genres since then (and you can hear a motif from this album used on Taylor Deupree and Marcus Fischer’s Twine).

Over the last seven or more years, I’ve become deeply involved with ambient/experimental works by composers such as Stephan Mathieu (who not only composes but masters others’ work at his studio) , Deupree (who established the influential ambient label 12K), and France Jobin, as well as those, like Ryuichi Sakamoto and Christian Fennesz, who dip in and out of the ambient genre.

In an age where we are bombarded with divisive and interruptive dialogs encouraging us to be outraged at every turn (not to mention the very real aspects of society that are worth our outrage, if only we had the time and energy to devote to them while being able to support ourselves financially), experimental ambient music allows me — on a good day — to reset my thoughts and tune into a more free-form sonic world. Ambient is not pablum. Ambient is not “new age music.” If anything ambient has been about transcending the boundaries of “instrument” and “technology”, something all genres of music have attempted at one time or another; hip-hop does this particularly well.

Here are some examples that have been influential for me:

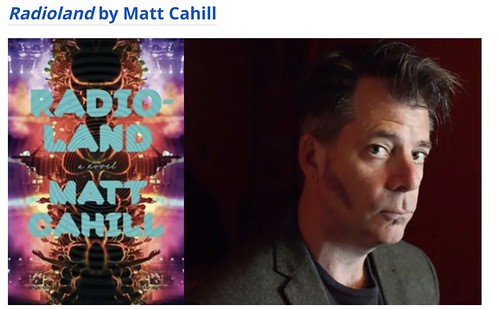

Radioland, by Stephan Mathieu: https://schwebung.bandcamp.com/album/radioland-2

Perpetual, by Ruyuichi Sakamoto / Illuha / Taylor Deupree: https://12kmusic.bandcamp.com/album/perpetual

Duo, by France Jobin + Richard Chartier: https://matterlabel.bandcamp.com/album/duo

~~~, anna roxanne: https://anaroxanne.bandcamp.com/album/-

Arrow, by Richard Youngs: https://preservedsound.bandcamp.com/album/arrow

Tracing Back The Radiance, by Jefre Cantu-Ledesma: https://jefrecantu-ledesma.bandcamp.com/album/tracing-back-the-radiance

Allister Thompson hosted a blog, Make Your Own Taste, that contains a lot of ambient artists and contextual information on the genre. You would do well to visit if this is your thing.

*note: I use the term “classical” generically; technically I prefer the Baroque and Romantic periods best, truth be told.